I was playing poker with friends online last summer as a way to do something together during the lockdown. I was surprised how difficult it was to find a good, free app where you could just play poker with your friends. They all seemed to have a catch - you play a few games for free but then you have to buy “tokens” or “gold” to play more. Even the apps from the main poker sites and casinos took “rake” or made you buy chips. I had imagined that there would be something like lichess out there where you can just play - after all you only need a deck of cards and to know the rules - it can’t be that difficult to make. So I set about making a prototype of a free and simple multiplayer poker app.

I wanted it to be free to play, accessible as a Progressive Web App rather than an Android or iOS app, and be as frictionless as possible - like lichess.org where you don’t even have to register an account, you can just go to the website and play. There’d be no money changing hands or ability to join games with people you don’t know - it’s all just played between friends with any money being sorted out privately.

Basic design

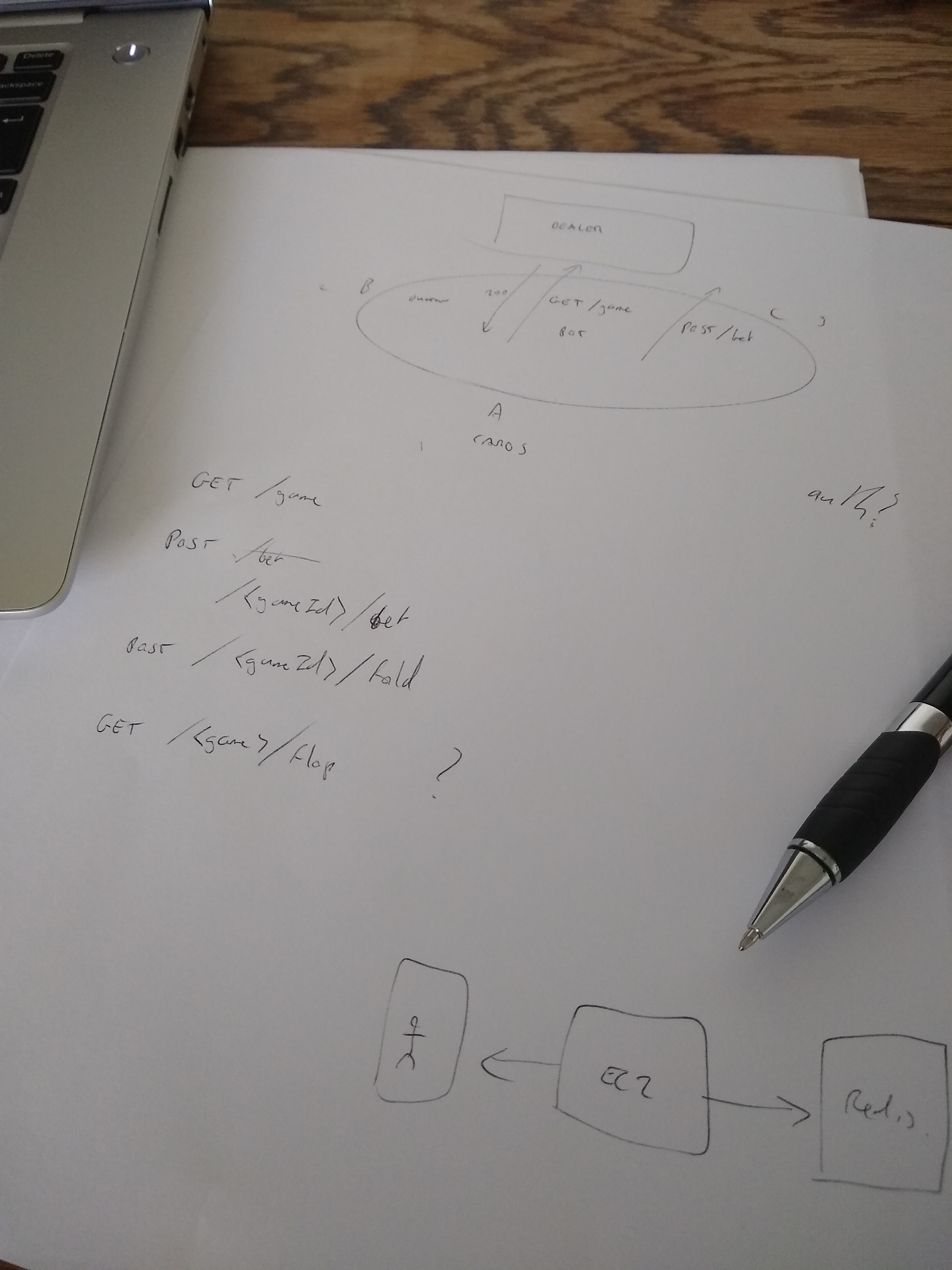

The first thing I did was sketch out on paper what actually happens in the real world when you sit down at a poker table. The essential things you need are a deck of cards, some chips, and knowledge of the rules of the game. I started with the basic idea: the table was the front end, players joined and left the table as they pleased and made decisions, and the dealer was the back end game server that knew the rules and dealt the cards.

I reasoned that the state of the game at any time is definitive - i.e. you don’t need to know the history of the game to know what to do next. As long as you had a list of players, their positions, their cards and chips, and whose turn it was next, then you could recreate the game at any point.

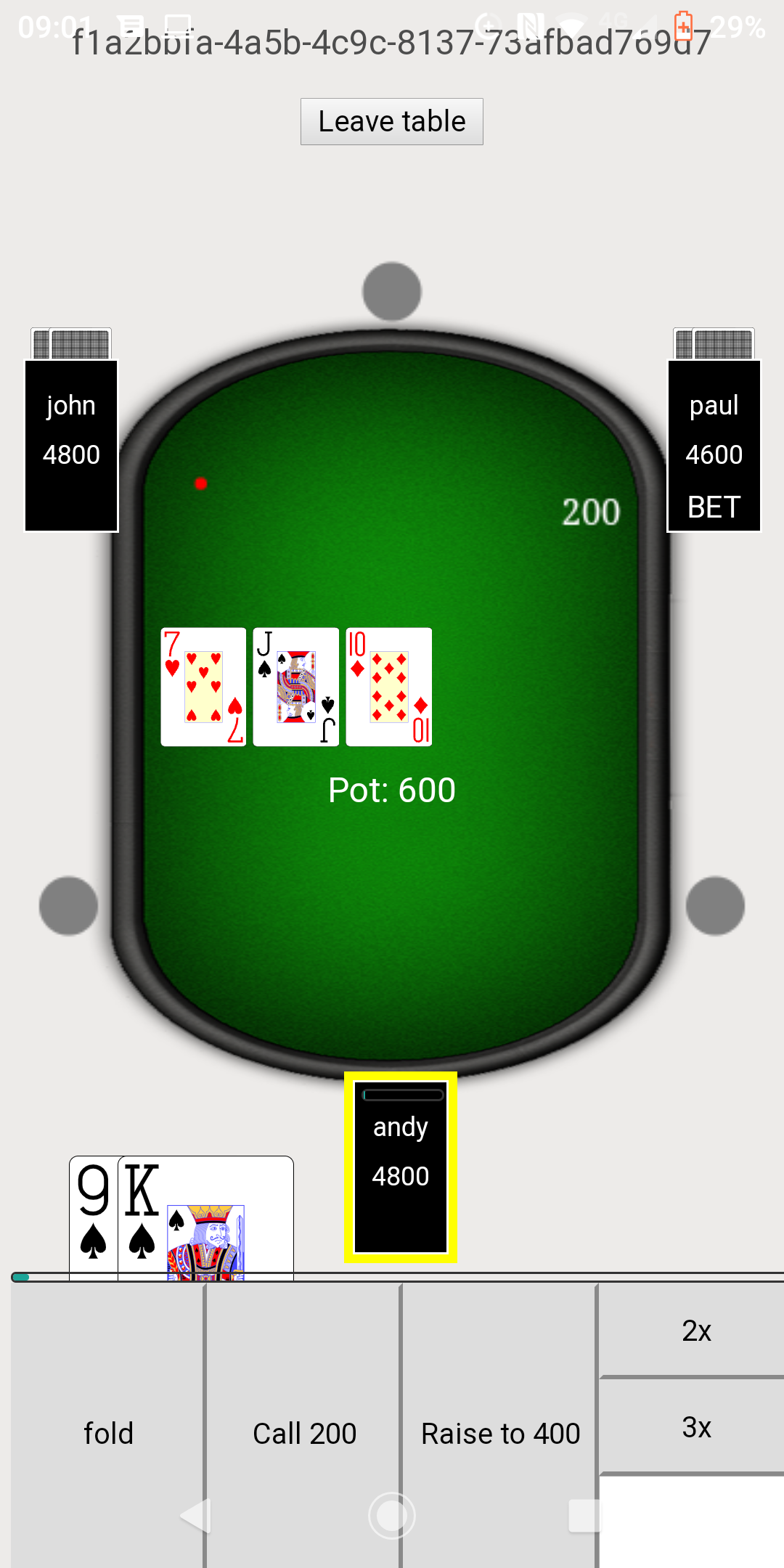

So my basic design was a front end that rendered the ‘game state’ visually and presented it to the players, a storage component for the current game state, and a server that received actions from the clients, modified the game state, and returned the new game state to the clients. This design was simple and decoupled, so for instance the game server could have many different clients - web apps or native apps - as long as they communicated over the same API.

Tech choices

The stack pretty much chose itself once I had the basic design. For the front end, components would be changing often and re-rendering in real time, and the front end was decoupled from the game server, so React was an obvious choice. The back end was just some exposed REST endpoints so any web framework would have done the job - I chose to use Python because I wanted fast setup and iteration and I wanted the development process to be as quick and as enjoyable as possible. At the time in my day job I’d been writing a lot of Java with Spring Boot, which can get very verbose and abstract, so it was a nice change to write some simple Python. I chose Flask as the web framework as the only thing I really needed was simple HTTP routing - everything else I’m happy to control myself, and Flask stays out of your way. For storage, an in-memory cache was the obvious choice rather than a database to store the game data. It would be read and written to every time a player makes a decision, and it needed to be fast and scalable - not for the prototype necessarily but if it were ever to be a real product. Also, the data doesn’t need to persist for too long - just the length of a game. I chose Redis as it’s what I know.

The Process

When you’re starting a new project you need forward momentum. I like to think of the development process as like a breadth-first search rather than a depth-first search. Your aim is to have the very first basic version of a complete working product; not to have 30% working perfectly and 70% not even started yet. For example if you’re working on the front end there is no point spending time making it look nice - just get it working and move on to the next thing. Making it look nice and polishing all the edges can come later. The design might get changed, the concept itself may not work, and if you’ve spent too much time on a particular feature that eventually gets deleted it’s just wasted time and ultimately wasted money.

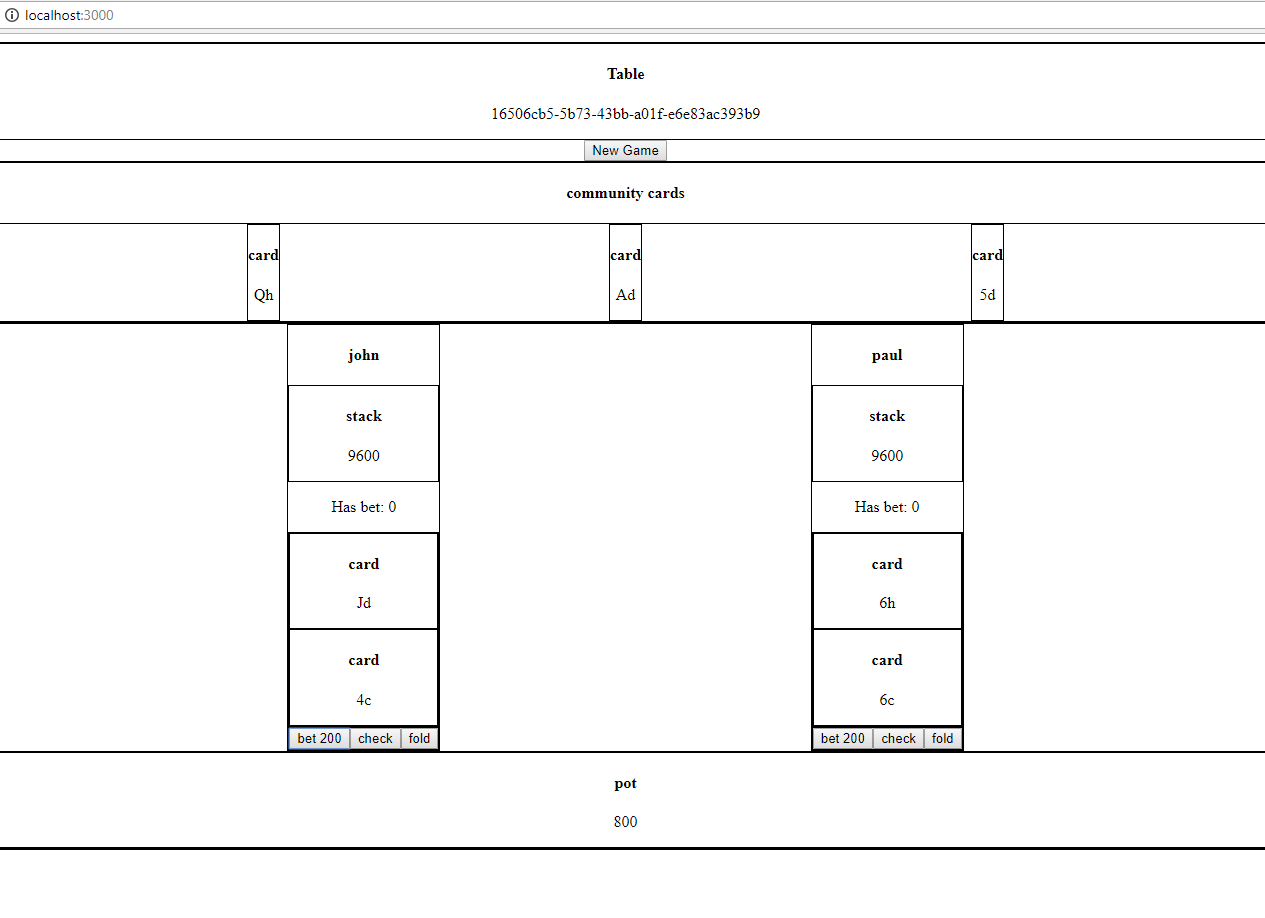

The first thing I worked on was the back-end API as this was the core. As soon as I had enough code in there to start hitting endpoints, I started running through a game of poker just using Postman, getting raw JSON responses back. As soon as this became laborious I made a very basic front end that rendered the game state in a more useful way than just raw JSON.

The logic to process the rules of poker is all my own except for the algorithm to determine the winning hand, given one or more pairs of cards and five community cards. The decision whether to use libraries or “roll your own” is a judgment call specific to each situation. It simply wasn’t worth the time or brainpower to write my own algorithm for determining the winning hand when I could just grab an efficient existing algorithm on GitHub. But the poker logic was core to the project, so it made sense to have full control and write it myself.

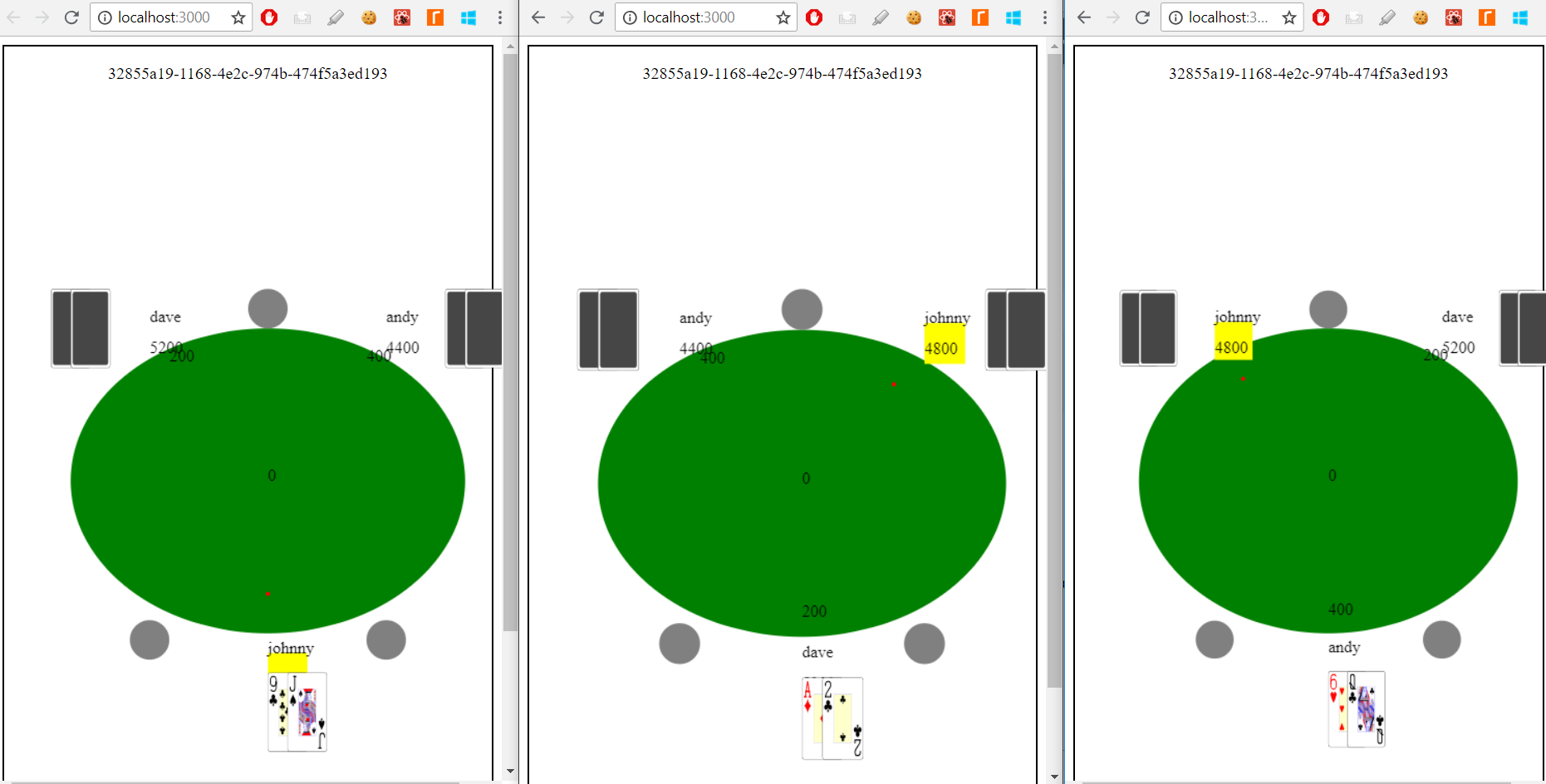

Once I had the server roughly working with one browser, I had to get it working with multiple browsers, and figure out how clients would receive updates - i.e. when a player made a decision like betting or folding how do other players receive that update. The traditional way to do this is to regularly poll the server, but I wanted something cleaner, so the choice was between Websockets or Server Sent Events. I chose SSE, mainly just by a quirk of how the project progressed: at the very start I had written the server with regular HTTP REST endpoints, without any concept of pushing updates to clients. When I got around to thinking about updating clients, Websockets would have meant a bit of rewriting since it uses a custom protocol, so I ended up keeping the regular endpoints for communication from the client to the server, and just used SSE (uses simple HTTP) to set up a one-way ‘subscribe’ endpoint. SSE also has features that Websockets lack such as automatic reconnection.

The next choice was how the server would handle multiple games at the same time. If one game state was updated, then only the connected clients who are in that game should be updated - not every client. Flask does have a feature where you can use the concept of “rooms” (the name comes from its use in chatroom applications), but that would tie a specific game to a specific server. I’m only going to have one server for the prototype, but I do want the option of scaling out in the future. If users were tied to one particular server then scaling across multiple servers would be tricky. And you’d need a way for every player in a game to go to the same server, which would be even more difficult. This is a commonly encountered problem in software development, usually when dealing with user sessions, which is solved by storing session data externally to the servers to maintain “session stickiness”. Although I’m not dealing with sessions here, I can use a similar principle to separate different games. Redis has a pub/sub queue feature, so a certain server can subscribe to the Redis queue for a particular game, and a different server can publish to that queue whenever it updates the game. Keeping the servers stateless allows for easy scaling in the future, and it just keeps things clean. You could even have an auto-scaling group that ramps the number of servers up or down based on the number of active users.

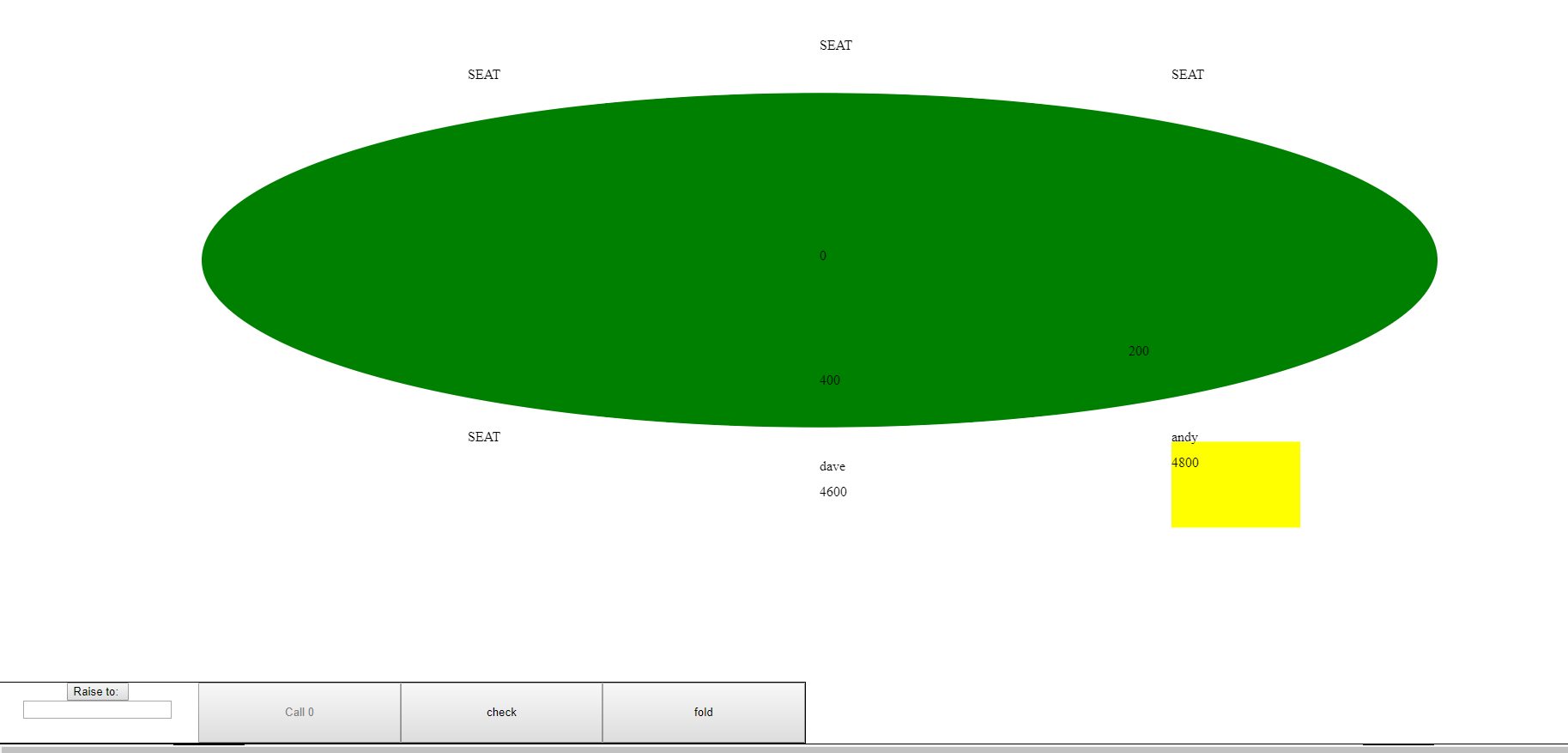

The last big design decision I had to make was whether to style the game using HTML Canvas or using plain old CSS. I actually started off using Canvas, thinking it would give me greater control, but actually I found the opposite to be true. I ended up developing a positioning system that got complicated quickly, and I ran into the usual Canvas scaling issues when rendering the card images, so I ended up rewriting a significant portion to use regular HTML elements styled with CSS instead of using canvas (for example the ‘boxes’ that represent the players at the table.

Security

One good thing about not collecting any user data or even having user accounts is that there’s nothing to steal. But there is the issue of players cheating - i.e. we need to avoid players seeing other players’ cards. Even if only one set of cards is rendered by the front end, someone with a basic knowledge of Chrome DevTools could get the full game state and see what cards the other players had. I prevented this by editing the game state before it was sent to a particular client. To prevent a techie sending fake HTTP requests to the server, pretending to be a different player, I generate a token when a player joins the game, that is sent only to that player, and that must be sent with every request to authenticate the player. This token is stored in Redis to maintain stateless servers.

The result

I finished the prototype in about 6 weeks over last summer, working on it one or two hours a day. If this was a proper project for a business I’d say it’d probably be a two to three week job. It’s hosted in Heroku on cheap infrastructure, so it has some latency issues now and again and it probably won’t handle many games at the same time. It has bugs - I didn’t have time to write tests so it definitely has bugs - but it’s a working prototype made in a few weeks, and that was the goal.

If you want to do what I did - learn to code and change your career - try my new course at learn.andydavi.es