In the previous post, we made a prototype of our basic idea – an application that allows you to share your book collection with others. Let’s say that the prototype has been approved by the customer and the project is going ahead. What’s next?

There’s no right answer to that, but my preference would be to set up the infrastructure and processes. By this I mean your servers, environments, storage etc, as well as your tools and processes for deploying your code. These things can take some time to set up, but it’s worth it to get it out of the way early as it will make the development process a lot smoother.

When we deployed the prototype in the previous post, I manually created an EC2 instance in the AWS Console, accessed the instance via SSH, uploaded the code from my computer, manually set up dependencies and the database, and started the application. That was fine to get a prototype up quickly, but we can’t be doing that every time we want to deploy a change.

You can find arguments online about the difference between Continuous Deployment and Continuous Delivery – these arguments just come down to the meaning of words. What’s important is the process itself, and when I say Continuous Deployment I mean that when I push my code from my local machine to GitHub, I want it to automatically be deployed to a testing environment, and if tests pass I want it to automatically deploy to production. This method isn’t appropriate in all cases – sometimes a manual approval will be required - but for my purposes I want it to be as simple and as automated as possible.

The plan in this post is to use AWS CodeBuild to get our source code from GitHub, build an artefact that we’ll store in S3 (Simple Storage Service), and use AWS CodeDeploy to deploy the application to a development environment. For now we’ll still set up the infrastructure manually, but eventually we’ll create a CloudFormation template to set up the infrastructure with one command. We’ll also soon add tests that will determine whether the application is deployed to a production environment.

Continuous Integration

My code repository of choice is GitHub, but there are plenty of others that do the same job. The first thing to decide on is a ‘branching strategy’. Strategies such as GitFlow are popular and solve a particular problem, but it’s important not to choose a tool or methodology just because it’s popular – we always need to think about our particular problem and how to solve it. In this case, there’s only a single developer, so we don’t need to worry about how to integrate changes from multiple developers at once. I also want to keep things simple – I always think you should start with the simplest possible solution and add to it later if we need to. I’m going to just use one main branch with feature branches merging directly to master. I don’t need a develop branch as it’s just me working on it (essentially my local branch acts as the develop branch), and I don’t want release branches. Master will always deploy to the ‘dev’ environment, where tests will be run, and if those tests pass it will deploy to the production environment. This isn’t standard – you wouldn’t normally run tests on dev for instance – but it works for me and it keeps my costs down by only having two environments.

Infrastructure

I’ll need to set up two environments – development and production, or dev and prod for short. For now I’ll just set up the dev environment as we’re not ready for prod yet.

First we’ll need a VPC (Virtual Private Cloud). For the prototype deployment in the previous post I used the default VPC, but I’ll set one up from scratch here, using the console. Within the VPC I’ll have a single public subnet, to expose the VPC to the internet. Ideally our database would be on a separate instance in a private subnet, but for now and as we’re not in production yet, a single public subnet will do. Eventually we might also have multiple public subnets and a load balancer, but that’s overkill for now.

Then I’ll create a new EC2 (Elastic Compute Cloud) instance, this time with an AMI (Amazon Machine Image) from the AWS Marketplace: Bitnami MEAN stack. This comes with Mongo, Express and Node already installed, so it saves me a job. I’ll tag the instance with the name “my-library-dev” so that CodeDeploy later knows where to deploy to. I’ll create a Security Group for the instance that opens port 22 for SSH, and port 3000 for HTTP (I’ll be using port 80 in production, but this will do for dev).

Unfortunately, when using CodeDeploy you must install the “CodeDeploy Agent” on your EC2 instance – it’s not on there by default. We can add a script to do this in the User Data section of the EC2 instance in the console:

#!/bin/bash -xe

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get -y install ruby

sudo apt-get -y install wget

cd /home/bitnami

wget https://aws-codedeploy-eu-west-2.s3.amazonaws.com/latest/install

sudo chmod +x ./install

sudo ./install auto

sudo service codedeploy-agent startWhen the EC2 instance first starts, this script will be executed and the agent will be installed.

The CodeDeploy agent needs access to S3, where our artefacts are stored. To give EC2 permission to access S3 we use an IAM Role and assign that role to the instance. The cost of this instance is roughly $0.01 per hour, which is about $8.50 per month. I don’t want to be paying for too many instances at this price, so I’ll eventually terminate the prototype instance and I won’t run the production instance until it’s ready. Ideally we’ll make the whole thing ‘serverless’ at some point and the cost will be close to zero.

The final thing to set up is our S3 buckets. One will be our artefact store, and the other will hold our .env file that holds the session secret and the Google API Key. For production, we might want to store these in Secrets Manager, but this will do for development. The bucket has restricted access, and the file is encrypted at rest and in transit.

Pipeline

A Continuous Delivery pipeline defines a series of steps that determines how your code is tested and deployed. I’ll be using AWS CodePipeline. It’s a fully managed service, which means that there’s no servers to manage like there would be if you hosted your own Jenkins server for instance, and it costs $1 per month per pipeline, so it’s good value. I won’t go through the detailed steps involved in setting up CodePipeline – instructions for that are easy to find.

Build

After setting up the ‘source’ of the pipeline and the ‘trigger’ – in our case the source is the master branch in our GitHub repository and the trigger is any change to that (detected using GitHub webhooks) – the next step is the build.

In a Java application the build would involve compiling the source and dependencies and packaging it into an ‘artefact’ – in Java’s case a jar file. Since we’re using NodeJS, and Javascript is an interpreted language, the build step isn’t as involved as that and should be quicker. We just need to install dependencies, pull in the .env file from S3 (these aren’t stored in the repository for security reasons), create an artefact in the form of a zip file, and store that artefact in S3.

I find that “Ops” work can often be a case of trial and error. It’s common to run into subtle edge cases, that only affect certain AMI’s, certain operating systems, etc. I ran into one such problem at the build stage, where I wanted to install the node dependencies. The installation was fine, but in short when the files were later copied to the server, the symlinks that npm sets up to find the modules were not copied across. Because of that I’ve moved the installation of dependencies from the build phase to the deployment phase. Running npm install on the instance itself also saves me storage costs in S3 and compute time in CodeBuild.

The build phase is defined in the buildspec.yml file:

version: 0.2

phases:

build:

commands:

- aws s3 cp s3://my-library-env-files/.env ./.env

artifacts:

files:

- '**/*'

name: my-library-$(date +%Y-%m-%d-%H:%M:%S).zipCodebuild has a free tier that gives you 100 build minutes per month. That should be more than enough for my purposes, but if I go over it’s $0.005 per minute.

Artifact store

Large teams and organisations often use a dedicated artefact store such as Nexus. I’m keeping it simple here and storing them in S3. I’ve set an expiry rule on the S3 bucket to delete builds older than 30 days. This will allow me to roll back if I have any problems, and in the unlikely event of needing a build older than 30 days I always have GitHub to build a new version from.

S3 storage costs $0.023 per GB. My builds are about 30KB, so I’ll be barely paying anything.

Deploy

AWS CodeDeploy uses a series of scripts that execute at defined points in the deployment. They are referenced in the appspec.yml file:

version: 0.0

os: linux

files:

- source: /

destination: /home/bitnami/app

permissions:

- object: /

pattern: "**"

owner: ubuntu

group: root

hooks:

BeforeInstall:

- location: scripts/stop_server.sh

timeout: 300

runas: ubuntu

AfterInstall:

- location: scripts/after_install.sh

timeout: 300

runas: ubuntu

ApplicationStart:

- location: scripts/start_server.sh

timeout: 300

runas: ubuntuFirst, we stop the server with the stop_server.sh script. I’m using the npm module ‘forever’ to start and stop the application:

export PATH=$PATH:/opt/bitnami/nodejs/bin/

forever stopall || true # true stops script exit code 1 (will stop deploy process) if no servers to stopThis will mean downtime for the app. For now, and certainly for the dev environment, this is fine. Eventually we might set up blue-green deployment for prod to achieve zero downtime. Once the files have been transferred to the instance, the after_install.sh script runs:

export PATH=$PATH:/opt/bitnami/nodejs/bin/:/opt/bitnami/mongodb/bin/

cd ~/app

npm installFinally, we start the database and the application with:

export PATH=$PATH:/opt/bitnami/nodejs/bin/:/opt/bitnami/mongodb/bin/

cd ~/app

sudo mongod --noauth --fork --logpath /var/log/mongod.log --logappend --dbpath /opt/bitnami/mongodb/data/db

sudo npm install forever -g

forever start src/index.jsThis database setup is far from ideal. Before we get this into production we’ll be splitting the database out into its own service, with either RDS or DynamoDB, but this will do for the dev environment.

CodeDeploy is free to use when deploying to AWS services.

Putting it all together

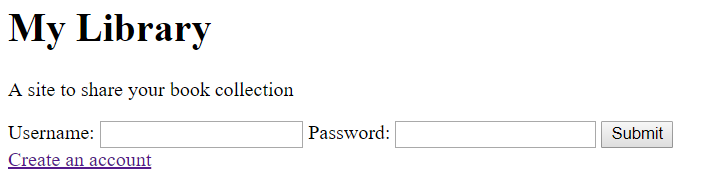

Let’s test that it all works. I’ll add this line to the login page:

<p>A site to share your book collection</p>Commit and push:

git commit -am "Add subtitle to login page - testing CD"

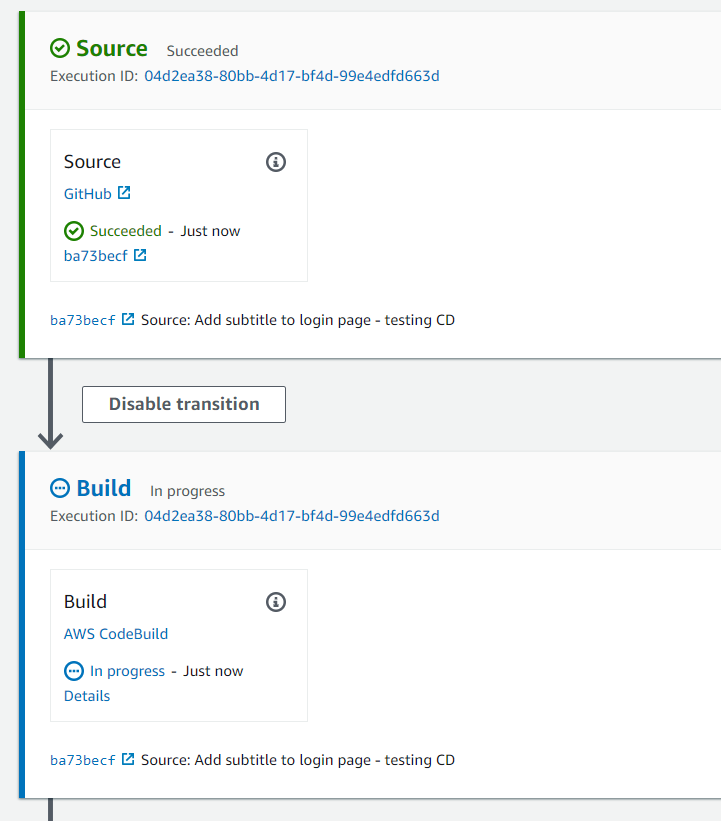

git push origin testing-cdThen I’ll create a pull request in GitHub and merge to master. If I then go to the CodePipeline console I can see that the pipeline has been triggered:

A few seconds later I see that the deployment has been successful, and if I go to my dev site I can see the change:

We’re now ready to develop features without having to worry about deployments. Once we’ve added tests, and we’re ready to deploy the first version to production, I’ll set up another pipeline to run the tests and deploy to prod.

You can have a look at the repository here, and the dev site here.